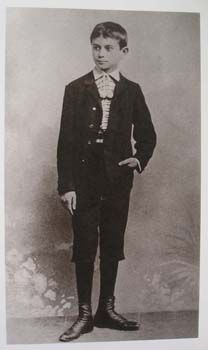

Having long wavered between his pro-Czech and pro-German inclinations, Hermann Kafka finally decided to send his son to a German school, most likely thinking he would thereby ensure him better prospects in life. Franz Kafka spent his first school years (1889-1893) in the German Elementary Boys’ School on Masný Trh (Meat Market) close to his home. The school was attended by children from middle-class German – overwhelmingly Jewish – families plus a minority of children from Catholic Czech homes, all of them from the Old Town quarter. The sons of the wealthier German and German-Jewish ‘City Park’ generally attended the more expensive elementary school run by the Piarists in Panská St.